How a Subtle Shift in Mindset Can Improve Performance

August 26, 2025How a Subtle Shift in Mindset Can Improve Performance

By Adam Jackson

B Shifter Buckslip, Sept. 9, 2025

I am a recovering perfectionist. I have spent the majority of my life as my harshest critic. I thought that setting high expectations—often unreasonable ones—would lead to success. While that mindset may lead to short-term gains, it comes at a price.

Perfectionists often suffer from a fixed mindset. You are either good at something or you’re not, and failure proves you’re not. If our goal is to do something perfectly, we often choose things we know we excel at. A fear of others seeing us fail holds us back and limits our potential for improvement. It’s like when they ask for volunteers at a drill. If you don’t feel you can perform the task perfectly, you definitely aren’t raising your hand. The last thing you want to do is confirm your fear that you just aren’t good at this task in front of a crowd. You meet feedback with defensiveness instead of seeing it as an opportunity for growth. Rumination about past mistakes and a fear of letting others down are often associated with this type of perfectionism.

A growth mindset is focused on continual learning. The voice in your

head changes from criticizing your performance to saying, “I am not good at that— yet.” This is a significantly different perspective.

A fixed mindset is especially challenging for officers. If we believe our abilities are static, then anything less than perfection is seen as failure. Our ego is the driving force, filling our head with negative messages. We want to prove more than improve. It is your ego that will keep you from drilling with your crew, convincing you it’s better to stay at the station and discuss training than to prove you can’t do something perfectly.

A growth mindset is focused on continual learning. The voice in your head changes from criticizing your performance to saying, “I am not good at that yet.” This is a significantly different perspective. The measure of success shifts to how much you are learning and how much you are helping others learn. Making mistakes is seen as the path to improvement.

How to Change Your Mindset

To change our beliefs about the nature of our abilities, we can utilize strategies highlighted by Eduardo Briceno in his book “The Performance Paradox.” He realized that mindset alone was not enough to actually improve skill, and hard work is not the only thing that leads to success. We need both the mindset that we can change, along with the methods to accomplish it.

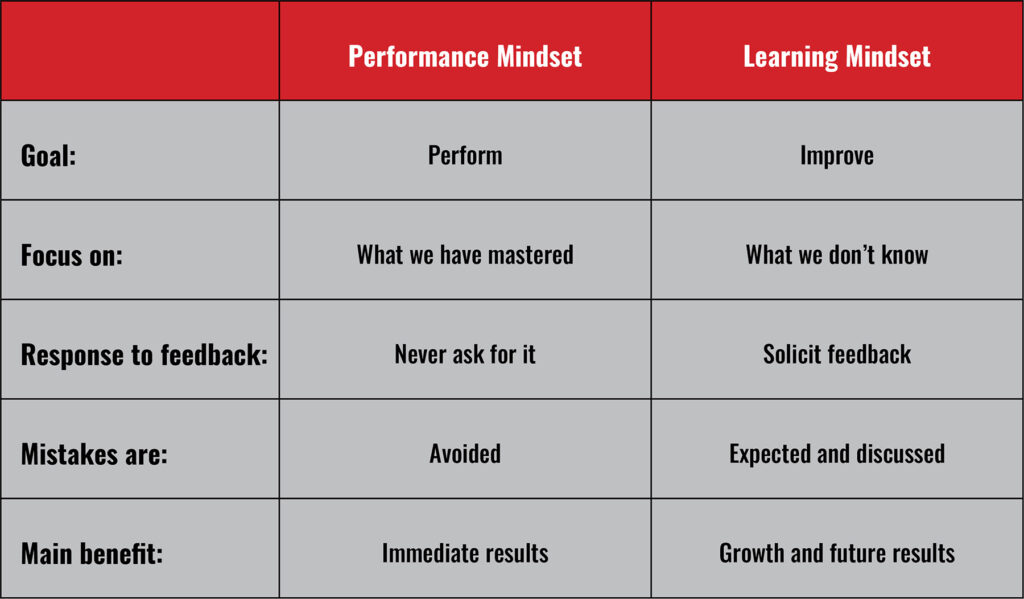

Fixed-mindset individuals often view everything with a performance mindset: Do the things you have mastered, avoid mistakes, stick with what you know.

The majority of our training time should be spent in the learning (growth) mindset. The performance (fixed) mindset is reserved for the emergency scene or a certification/promotional environment. When we get promoted, many of us feel like we should know everything about the previous position we held as well as the new one. We’ve doubled our expectations of ourselves and believe we need to meet them all perfectly. Our inner voice adds even more pressure to perform. We’d never think of asking a firefighter for feedback because we think we should know it all. Below, I share two methods to help you shift your mindset and step into the learning zone.

No. 1. Practice Deliberately

Using a deliberate practice method developed by psychologist Anders Ericsson, you focus on tasks that are just beyond what you can currently do. Each step in the process is broken down into component skills. You then identify what components you are working to improve. Next, you perform the task with your crew members watching—even recording if possible—to help determine the issue that seems to be causing you difficulties. An example of this could be a firefighter who wants to become an officer. While the role of officer may seem overwhelming when you think of all the things one has to be good at, you can break the job down into key skills and tasks. You then have the firefighter work on an individual skill, such as incident command for the initial arriving officer. This can be broken down even further into sub-skills such as understanding critical fireground factors. Once they have completed that, you move on to the next skill. Developing an individual training plan will help you and your firefighter stay on task and help ensure their success.

No. 2. Work Smarter, Not Harder

When we are learning a new task, we usually improve our performance, which reinforces the concept of continual practice. This works until our skill hits a plateau. We think we simply need more practice. If I pull the bulk load 100 times (perform), I will become perfect at it. If you are not focusing on the right steps, you are working harder at the wrong things.

Let’s use deploying hose from the rear bed as an example. You might be really fast from the cab to the hosebed, but slowing down once you have cleared the hosebed. Or maybe there is a problem flaking the hose out correctly. Once you isolate the challenge(s), you can ask for feedback, then perform that portion of the task repeatedly. You can change your method or try it again, each time asking, “What did I learn from that?” If you don’t stop and identify what the issues are, you will continue to perform the drill with no real improvement. This will invariably lead to frustration.

Small Changes Deliver Big Gains

I am not saying you shouldn’t perform the task the way your department expects it to be done. This is about small changes that allow you to do it better. It might be the foot you step onto the hosebed with, the shoulder you place the hose on or the way you are grasping the hose. Maybe you’ll realize you need to improve your strength to complete the task correctly. Reflection is the key to learning while doing.

Officers should have an annual improvement plan for themselves and their crew. The key question is, “What abilities or skills are we going to focus on this year?” This is much more than just doing the department’s assigned training. Officers know their crews on a much more personal level than the training division ever will. The trust you build within your crew should create an environment where everyone feels comfortable asking for feedback. Combined with personal reflection, that feedback becomes the key to greater success.

Adam Jackson works for Central Pierce Fire & Rescue in Washington. He was a firefighter for 12 years and a company officer for 10. For the past several years, Adam has served as a chief officer. He is currently the deputy chief of performance. In his off time, Adam enjoys cycling, camping and spending time with his family. You can reach Adam at ajackson@iaff726.org.