The One Where We Try to Save a Parrot: The fire department earns community trust whenever we show up—especially for creatures great & small.

August 25, 2025The One Where We Try to Save a Parrot

The fire department earns community trust whenever we show up—especially for creatures great & small.

By Johnny Peters

B Shifter Buckslip, Aug. 26, 2025

A guy walks into your station and asks for help getting his family’s parrot out of a tree.

Does this fall within the scope of your duties?

“No” is the wrong answer. If you find yourself disagreeing with me and providing a list of reasons why in an imaginary argument, then read on. If you answered yes, you have already passed this week’s CE and may pick up your coffee on the way out. Thank you.

Let’s get on with it.

I admit the question isn’t exactly fair. But life isn’t fair. Animal fetching exists at the edge of our job. It is a gray zone. We won’t be charged with dereliction for refusal. What isn’t gray at all is that people expect us to help them. Community trust in the fire service has been built up over the centuries. I’ve written about it, and so have many others. Some things bear repeating. Just like knot-tying is a perishable skill, trust is a perishable resource. Obviously, you have to try to save the parrot.

I answered the question recently by taking an engine and ladder company to the site of a parrot in distress. A guy walking into our station had asked if we could help him rescue the family’s pet bird. We communicated by typing on his phone, to overcome his hearing impairment and my properly groomed Fire Service Mustache®

We remained in service, in part because we can’t neglect a structure fire or someone having a heart attack to save an animal, but also because NFIRS deleted “Parrot in Tree” with its latest update of call types. The entire dispatch system would crash if they tried to create that record, returning us to carrier pigeon dispatch for the foreseeable future. Risk vs. benefit, and all that.

Rescuing pets that aren’t in danger may not be in our job description, but it’s part of our lore—and a big reason people see us as the good guys.

The parrot was up a tall pine tree. I’m not sure how tall because I’m accustomed to measuring height by counting windows. We set up the aerial, dealt with the parrot’s mother (adopted—she was not also a parrot), who was upset that she couldn’t be the one to climb up there, and nodded thoughtfully when told to be slow. We sent the rookie up with gauntlet gloves, a helmet and the parrot’s backpack. It was not a backpack for the parrot to wear, but for the parrot to travel in. It had a plastic viewport so the parrot could see the world as the mother walked around outside. It was likely an unintentional form of psychological torture.

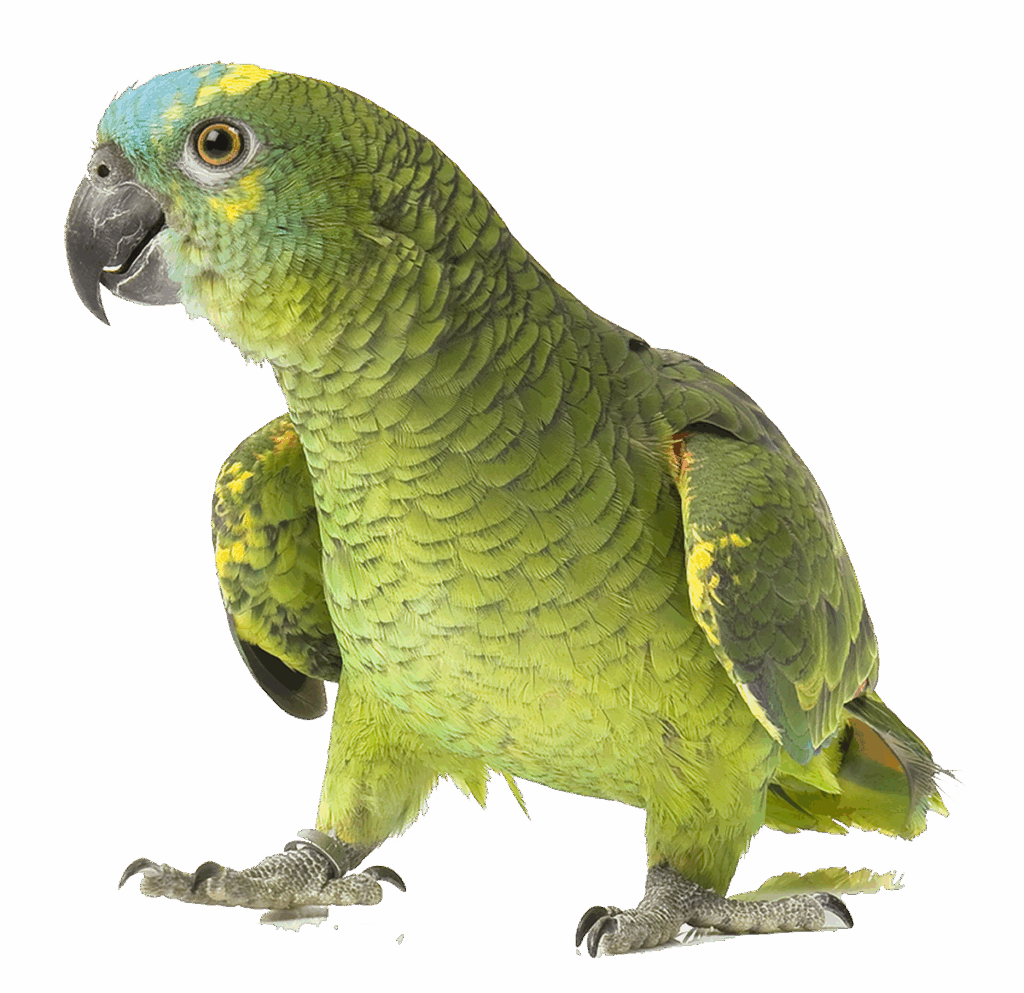

The parrot wasn’t as large as I’d hoped. In my experience, the smaller the bird, the more skittish. It was larger than a parakeet, but smaller than a macaw, favoring the parakeet side.

My visions of the creature hopping willingly onto the gauntleted rookie’s wrist had all but evaporated. But the owners were confident it would see the backpack as refuge from the swaying pine branch to which it had been clinging since its escape, and this confidence spread to the rest of us.

We were—all of us—deceived. The bird, of course, took flight.

It bolted from the tree and circled overhead, flight wobbly in the wind. It continued to circle, and seeing people near its new home in the tree, flew in a widening, crazed gyre, its altitude slowly decreasing. The domestic creature had little in the way of gas in its feathery fuselage. At last, it dropped out of sight, some four houses down on the opposite side of the street.

I wondered how soft the landing was. An out-of-control parrot might land anywhere, and Houston is the domain of many dogs and an award-winning feral cat population. A plump parrot with a heaving breast would prove a tempting squeak toy or snack. We had to pivot from aerial ops to ground search.

We moved with purpose down the street to the likely crash site. I was praying for unlocked gates and yards free of protective canines. The only thing more tempting to a dog than a downed birdcraft is a man in ripstop trousers. They appreciate the challenge.

As I closed in, a minivan whipped into a driveway ahead. The doors opened simultaneously, disgorging a family. In hindsight, they moved like a SWAT team on a raid, and I should have known I was looking at a family-deployed rescue team. But at the time, I attempted to hail them to gain vital information about access and Known Mammalian Hazards (NFIRS, Entry 37). They ignored me. A woman in house shoes passed me on the right. The rescue team had slipped past me.

I heard squawking. A kid from the minivan bolted from the front door. He was a herald announcing the successful bird recovery. The bird had found its own backyard.

Officially speaking, getting a family parrot out of a tree isn’t our job. … But most people look to us as the good guys & that’s thanks to the work of thousands of people, some of whom have died while building up this goodwill.

I looked back to see demobilization underway. The aerial was nested, and the outriggers were serenely retracting. I can’t list all the items in our after-action review. I’ve chosen at random Item 53: The Primary Owner was grumpy and didn’t say thanks. Response: People aren’t at their best in crisis. Primary Owner (PO) was probably angry at whomever released the Parrot in Question (PiQ)—possibly PO herself—and first responders are a safer target than family. And she asked how much the call would cost. But she was out of sorts. No one told the customer life was gonna be this way. It is advised to never expect gratitude and adopt the mindset that all we are owed is contained entirely in our Total Compensation Package®. Expecting more leads to resentment, resentment leads to a bad attitude, and a bad attitude is the path to a formal complaint.

Officially speaking, getting a family parrot out of a tree isn’t our job. There is an NFIRS entry for animal rescue, but this is only when it’s in immediate danger of death, not merely escaped from owners. But most people look to us as the good guys, and that’s thanks to the work of thousands of people, some of whom have died while building up this goodwill.

I’m not Saint Francis. I have this job because it’s fun. But I feel like I owe it to those who have gone before to maintain that goodwill or, at the very least, not to screw it up because some official job description written by a bureaucrat doesn’t mention the non-emergent aid needed in the moment. We don’t have to go out of service for it. We probably don’t even have to succeed.

But we do need to show up.

So if someone in need asks you to help them recover their escaped parrot, turning them down is the wrong answer. What’s the right one?

“Sure, where?”

Johnny Peters has been with the Houston Fire Department since last century. In this time, he has successfully gamed the system and was promoted to senior captain, forever freeing himself of the burden of fire hose by hiding in a truck company.