The Great Divide: Our sameness should unify us, but institutionalized differences tear us apart.

July 12, 2025The Great Divide

Our sameness should unify us, but institutionalized differences tear us apart.

By Nick Brunacini

B Shifter Buckslip, July 15, 2025

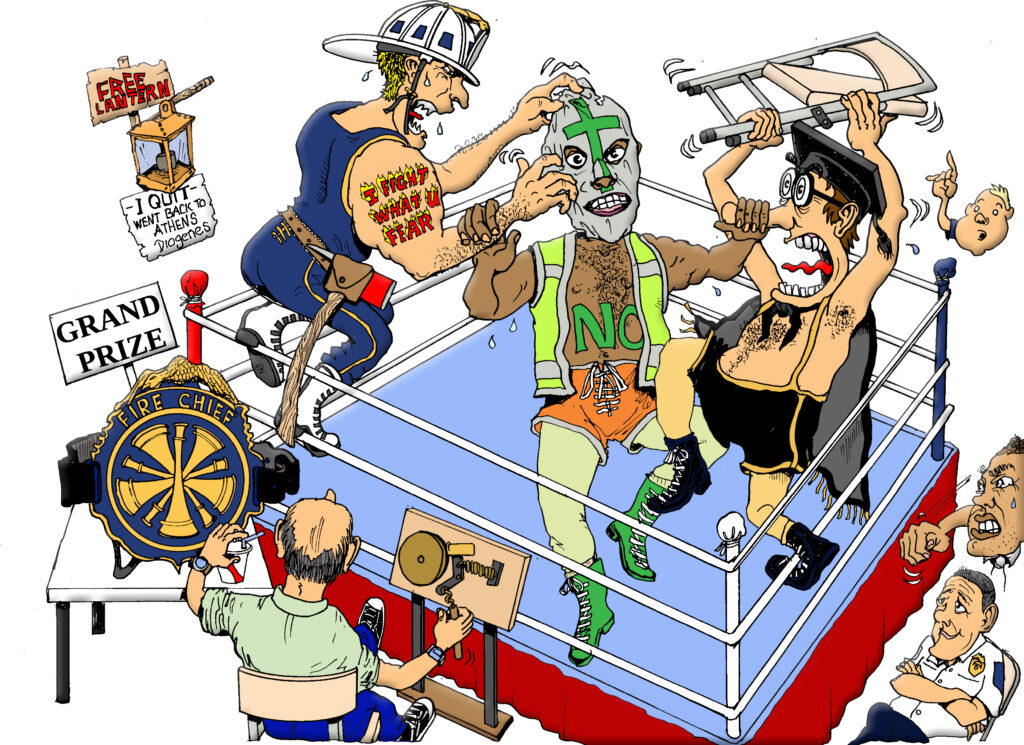

There are a lot of stratificators in the fire service—values, beliefs, traits or other differences that create separation among members. Stratificators are typically used to cause division and turmoil. The most well-known stratificators are the shifts—A, B and C—which have been divided into unique personality disorders, e.g., “Hi. I’m Nick. I am a B-shifter and dislike overt displays of authority. B-shifters thrive by hurling their bodies into burning property!” Another stratificator is the number of battalions that make up a fire department; my former government employer had eight.

The combination of working a 40-hour week, being an assistant or deputy chief in charge of ops, training or safety, and competing for a soon-to-be vacant fire chief’s position produces a giant, sucking black hole of stratification.

One would think their inherent B-shiftness would unify all B-shifters—after all, a McDonald’s Big Mac is universally consistent across franchises—but this theory goes out the window when you assign B-shifters to different battalions. What we end up with are three shifts split up among eight battalions, producing 24 different (or stratificated) fire departments. Stratifcators are like dark energy that causes solid objects to pull apart from one another. It would seem each shift should be aligned by its sameness: A-shifters create their own beauty, B-shifters bond over rebellion and C-shift uses its love of order to self-herd. Not so in fire departments, where the shift is the same, but the battalions are different. Battalion chiefs compound this stratification when they allow personal pet peeves to drive their supervision and leadership practices instead of the employee-mandated systems developed to keep service consistent—like a Big Mac.

14 Bugles of Separation

The traditional fire department org chart is full of stratificators. Let’s first consider that over 90% of fire departments work a 24 hours on/48 hours off work schedule to deliver service 24 hours a day on the task, tactical and strategic levels. Despite this operational truth, more than 90% of a fire department is managed by the administrative staff, who work a different schedule than the service-delivery providers.

My former government employer used an administrative model to manage the entire operations division. The fire chief (five bugles) worked a 40-hour week, as did the operations chief (four bugles). The eight district commanders (three bugles) who reported to the ops chief worked a 40-hour week and managed all 24 battalion chiefs (two bugles). BCs worked the same 24-hour shift schedule as the operations division. This system allowed the fire chief, ops chief and all eight of the district commanders to meet at any time of their choosing because they worked the same schedule. They could also meet with the other four divisions: logistics, personnel, medical services and training. Of these, training and safety (under medical services) produced the greatest levels of stratification from the operations division. Staff vs. line becomes more stratified when we include the personal goals of the department’s ranking members (all working staff jobs); the combination of working a 40-hour week, being an assistant or deputy chief in charge of ops, training or safety, and competing for a soon-to-be vacant fire chief’s position produces a giant, sucking black hole of stratification. (This is probably the wrong forum to discuss the stratification math of intimate, off-duty relationships between members of the workgroup.)

Everyone’s an Expert, But No One’s in Charge

Stratifications resulting from misalignment between the training and ops divisions create operational disconnects ahead of service delivery. For example, consider the new research developed by NIST and UL during the last few decades. Let’s say a department has a training division that wants to teach best firefighting practices based on that research, including new exterior water application tactics as an element of the offensive strategy, as well as coordinating ventilation with fire control. The training division develops a class to teach these concepts, but it quickly erupts into arguments with certain members of the operations audience defending existing tactics. The ops chief soon inserts themself into the fray to represent the old way (or some other way that counters the training division’s new approach). This produces stratification between members of the fire chief’s own staff—a product of three “experts” (fire chief, ops chief and training chief) having different expert opinions on the same subject. Everything turns into a rank-based power contest of who is in charge of the fire department, and the only one who can unstratify the situation is the fire chief. But being a fire chief has a lot in common with being a parent—not everyone should be one.

The problem is our industry has spent the last 50 years stratifying structural firefighting; this doesn’t happen in the EMS, hazmat or tech rescue worlds because those service-delivery types are standardized and regulated. A firefighter can be a paramedic anywhere, but a battalion chief can only manage structure fires in their own department. This is a major reason the operations, safety and training divisions are stratified. Disconnects between ops and training produce confusion regarding the actions taken ahead of the fire, along with the timing and sequence of those actions. We’re in the land of dinosaurs vs. modern tactics. The only solution is tactical clarity from the fire chief.

Operational Dogma & Tactical Cults

A simple fire attack becomes as divisive as religion. Do you believe in rapid fire attack or searching ahead of all other task-level activities? Maybe you’re a fundamentalist who worships vertical ventilation, or someone whose rituals include orbiting in a clockwise motion and breaking windows with a long pike. (Instead of spending another one thousand words screaming into this tactical void, let’s defer final thoughts on this subject to Frankenstein, who famously said, “Fire bad, water good.”) There are so many stratificators that they should be listed on the apparatus inventory. Firefighting stratificators are the loudest, which explains why a minority of worshipers can make so much noise. Many of these tactical sages end up preaching on random street corners, shouting into the sun while wearing their “It’s worth the risk” T-shirts. The rope whisperers never argue over knots.

Leadership Decreed Unity Upon the Department—and It was Good

In many instances, the task-level officers and the ops chief are aligned with the department’s current tactics. In this case, the training division becomes the outlier with their new, improved (and safer) way of doing business. This is because the training division rarely shows up to the incident scene. This allows the training division to testify against the ops division when something goes wrong at the incident scene. The safety division on the other hand responds to working structure fires. This response has the capability of stratifying a current incident operation. The best example for this occurred to me during a multiple alarm fire in a large commercial structure.

We had a full alarm assigned at a fire in a commercial structure that included a dozen separate occupancies. We had enough task-level units working but were awaiting BCs to arrive so they could manage the two to three active attack positions. When the first safety officer arrived to the incident scene, he came over the tactical radio channel and gave us a good description of conditions on the Charlie side of the structure. When he finished his report, I communicated, “Copy North District Safety. I want you to assume Charlie Division.” The safety officer replied, “That is negative, Command. I will not be assuming any tactical-level assignment.”

Ten minutes later, we brought the fire under control. Five minutes after that, I left the command post to find North District Safety and explain the difference between a shift commander (the ranking on-duty officer) and a North District captain assigned to the safety division. I shared that the safest thing he could do in the future is to take over managing the tactical level for the Charlie Division when the IC orders him to do so. He went on to grieve that the assistant chief in charge of the safety division told all the safety officer minions never to take or follow any order from the IC. Their job was to make sure the IC didn’t injure or kill firefighters, and they were our overlords. Once he was done with his stratifying excuse, I finished our early morning conversation by establishing the understanding that if he ever showed up to the incident scene and behaved in that manner again, the IC would order a ladder crew to pummel him; after recovering from his re-education, he would be assigned to an ambulance for the remainder of his career.

It creates tactical confusion to put three different sections in charge of the same activity. There’s a reason we manage incident operations with single a IC, which brings me to the simplest remedy for stratification: unification. My government employment became unstratified when the leadership of our department threw in the towel and “embedded” both safety and training into the operations division. You would think this caused more work for the ranking officers in ops since they had both safety and training responsibilities on top of their already existing operational duties. The opposite was true. It required less work and time and reduced headaches. The adventure began with reorganizing the department around the service it delivers. We replaced staff district commanders with shift commanders who worked a 24/48 shift schedule.

This change was the first major step in de-stratifying our department. This effort also resurrected the rank of battalion chief. Under the old, stratified organization, the BC position was like a bastard child no one wanted. Company officers are members of the bargaining unit and have a defined set of personnel rules and regulations concerning their employment benefits and rights. Members promoting from company officer to BC lose these rights. Before the reorganization, newly promoted chiefs would work a maximum of one to three years in the field as a BC before eventually being reassigned to a staff position where they would become a “real” chief. Our department viewed BCs as shift worms who would eventually turn into a beautiful staff butterfly. Funny, but embedding safety and training back into the operations division took the BC’s job from the worst to the best position in the fire department.

Stay tuned for the next article in this series, “Going from staff deputies to shift commanders.”

Additional articles will cover:

- The fourth deputy.

- Embedding safety.

- Taking back training.

- Utilizing after-action reviews to drive change.

Nick Brunacini joined the Phoenix Fire Department (PFD) in 1980. He served seven years as a firefighter on different engine companies before being promoted to captain and working nine years on a ladder company. Nick served as a battalion chief for five years before promoting to shift commander in 2001. He then spent the next five years developing and teaching the Blue Card curriculum at the PFD’s Command Training Center. His last assignment with the PFD was South Shift commander. Nick retired from the PFD in 2009 after spending the first 26 years of his fire-department career as a B-shifter and the last three on C Shift. Nick is the author of “B-Shifter—A Firefighter’s Memoir.” He also co-wrote “Command Safety.” Today, he is the publisher of B Shifter and a Blue Card instructor.