Support officers aren’t just drivers. Learn how & why to utilize these unsung heroes of incident command in your department.

October 29, 2024Support officers aren’t just drivers. Learn how & why to utilize these unsung heroes of incident command in your department.

By Steve Lester

B Shifter Buckslip, Oct. 29, 2024

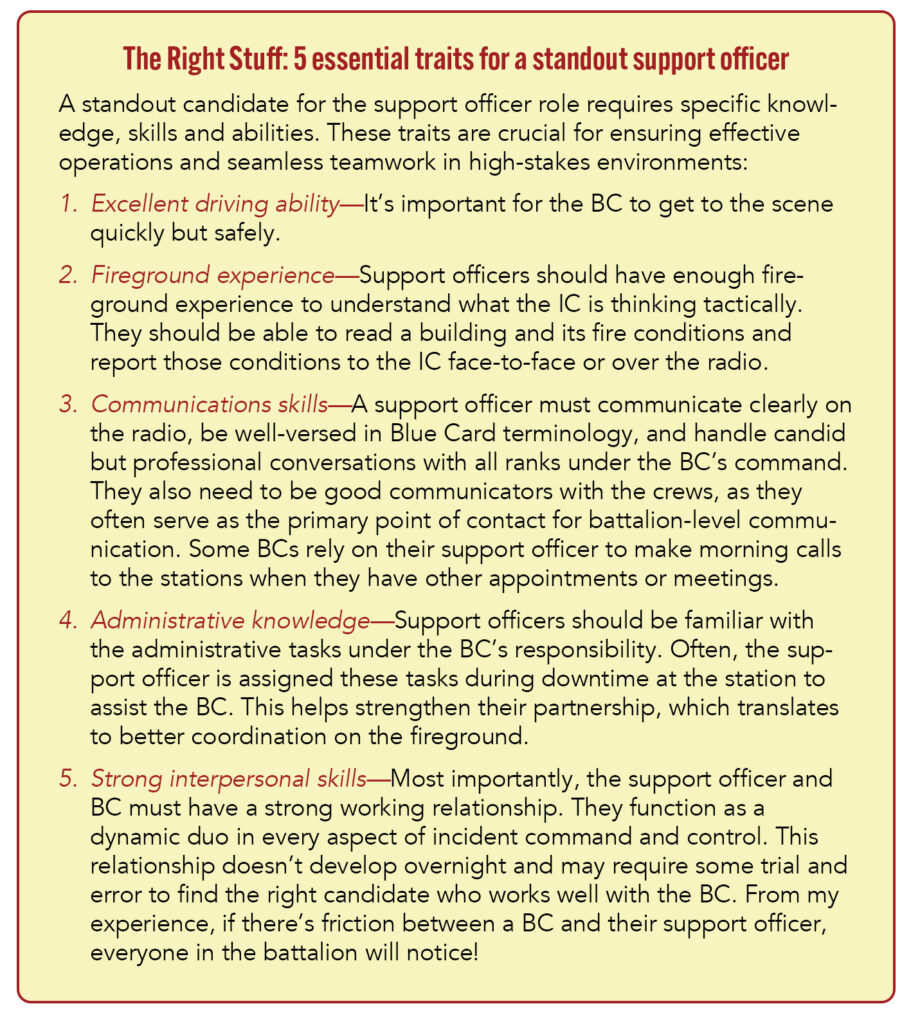

For the past 12 to 18 months, I have traveled nationwide conducting train-the-trainers, mayday workshops and certification labs. Everywhere I go, people have questions about the support officer’s role and where they fit into an incident. Are they permanently assigned to the battalion chief as an aide? What are their exact duties on the scene of an incident? What rank do they hold? What responsibilities do they have when not responding to an incident? I admit, both students and fellow instructors like to tease me about my fire department’s commitment to the support officer program. (Jealousy is an ugly thing!) Spend a few minutes with me as I explain the support officer’s vital role in day-to-day operations and how your life as an incident commander will change forever once your organization adopts this concept.

My organization’s journey with support officers began in the early 2000s. In the post 9/11 world, as we dove deeper into NIMS, incident management and accountability, we became painfully aware that our BCs (aka, incident commanders) needed help tracking resources and maintaining accountability in the command post. The department selected a group of 12 personnel (four battalions and three shifts) at the rank of firefighter II to serve as drivers who would assist the BC in the command post. (My department refers to these positions as field techs.) Our initial group of 12 comprised mostly senior firefighters who had chosen not to be promoted but had many years of task-level fireground experience. We required them to complete a specific incident command curriculum, including the National Fire Academy’s Incident Safety Officer course, public information officer training, and several NIMS classes. When they completed this training, we awarded them the rank of Firefighter III and a stipend for their trouble.

Initially, the field techs were the first to be redeployed to cover staffing shortages, often filling in at outlying stations during sick-outs. After two years of trial and error, the value of these positions became increasingly clear, one incident at a time. In 2018, when we transitioned from the standard NIMS command style to the Blue Card program, the need to pair field techs with BCs for division operations became even more evident. In 2020, the COVID pandemic forced our department to create an apparatus reduction matrix to manage significant staffing shortages as employees were exposed to the virus. The matrix outlined 10 steps of reduction in order of priority, with one being the lowest priority to keep in service and 10 being the highest. Step 9, second only to shutting down our heavy rescue vehicle, involved removing field techs from the battalion vehicle to staff other rigs. This highlights our department’s commitment to the field tech program and its crucial role in incident command and control.

You might think, “My department will never go for this.” Just stick with me, and I’ll help you sell the support officer concept. Here are just a few of the ways our support officers provide relief for our BCs on a daily basis:

1. Support officers are the battalion’s primary drivers, handling morning vehicle check-offs to ensure it is clean, maintained and mission-ready. This allows the BC to focus on staffing, communicate with officers and plan the day’s activities. Most importantly, having the support officer drive to an incident enables the BC to concentrate on radio traffic, note assignments and resources, and develop situational awareness. This facilitates a seamless command transfer and reduces the strain on the mobile IC (IC No. 1) by eliminating the need to repeat their assignments to the strategic IC (IC No. 2).

2. Upon arrival, the support officer assists the strategic IC by tracking resources and updating the tactical worksheet. My support officer and I each maintained a worksheet: I typically used the department’s formal worksheet, while my support officer tracked resources on a notepad as a backup. (One support officer I worked with preferred using an accountability board in the command post, and he did so effectively.) This duplication of effort proved valuable on several occasions when I missed a resource moving from one assignment to another. There are also times when you need eyes on a specific area of a structure, such as the basement or the Charlie side. Having a support officer allows you to stay in the command post while they investigate the location. They can either return with a CAN report or communicate via portable radio. For these reasons, support officers should have extensive fireground experience—you need someone who knows what to look for and what to report.

3. A support officer adds another set of ears in the command post to monitor the tactical frequency or any other channels your organization uses. In my organization, we operate on an 800 MHz trunked system, but when entering certain buildings, such as high-rises or underground concrete structures, responders must switch to a direct frequency (I-TAC) for radio-to-radio communication. Having an additional person in the command post ensures that two individuals can monitor both frequencies, reducing the chance of the IC missing critical radio traffic, especially priority calls or maydays.

4. The IC’s ability to concentrate on the incident is paramount, and support officers are great for running command-post interference. My major pet peeve when I command an incident is when someone comes to the command post to speak with me. My field would re-direct anyone approaching the command post to his side of the vehicle and tell them, “Chief doesn’t want to talk to you right now.” During an incident, a support officer can also serve as a liaison between the fire department and the homeowner or business owner, gathering demographic information, assessing a family or business’s needs, and requesting any necessary assistance, such as the Red Cross or a board-up company. When these tasks are taken off the IC’s shoulders, they can focus on other things.

5. The support officer is a great advantage on the fireground when a BC is assigned to a division supervisor role. From a tactical perspective or as an embedded safety officer, they serve as a second set of eyes in that division. The support officer also manages accountability for that division, tracking resources, managing entry times and ensuring crews are recycled properly between rotations. Sometimes, you may need them to be the traffic cop and keep crews from trying to creep into the hazard zone.

If your organization doesn’t currently use the support officer or support officer position, I hope these points encourage you to bring it up with key decision-makers. In my organization, it ultimately came down to fireground safety and accountability—any fire chief worth their weight in salt should pay attention to ideas that support those priorities. If they seem uninterested, propose a trial run: Assign a support officer to a BC for six months, then assess the impact on their performance at emergency scenes and in the battalion’s day-to-day operations. By the end of the evaluation, they’ll clearly see the incredible value of these roles. Best of luck, and remember to make a difference!

Steve Lester is a division chief with Cobb County Fire and Emergency Services near Atlanta. He became a career firefighter in 1996 and worked his way through the ranks. Steve has degrees in fire management and nursing; he has served his department as a paramedic, special operations medic and Blue Card Instructor and works as a registered nurse. Steve assisted his department with developing recent editions of the “High-Rise Operations Manual” and the “Incident Management Manual.” Steve has been a speaker at the Metro Atlanta Firefighters Conference and is a senior advisor for the 575 F.O.O.L.S.